Chester A. Arthur

| Chester A. Arthur | |

|

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office September 19, 1881 – March 4, 1885 |

|

| Vice President | None |

| Preceded by | James A. Garfield |

| Succeeded by | Grover Cleveland |

|

|

|

| In office March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881 |

|

| President | James A. Garfield |

| Preceded by | William A. Wheeler |

| Succeeded by | Thomas A. Hendricks |

|

|

|

| Born | October 5, 1829 Fairfield, Vermont |

| Died | November 18, 1886 (aged 57) New York, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Ellen Lewis Herndon Arthur, niece of Matthew Fontaine Maury |

| Children | William Lewis Herndon Arthur Chester Alan Arthur II Ellen Hansbrough Herndon Arthur |

| Alma mater | Union College |

| Occupation | Lawyer, Civil servant, Educator (Teacher) |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/branch | Union Army |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Unit | New York Militia |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was an American politician who served as the 21st President of the United States. Arthur was a member of the Republican Party and worked as a lawyer before becoming the 20th Vice President under James Garfield. While Garfield was mortally wounded by Charles J. Guiteau on July 2, 1881, he did not die until September 19 of that year, at which time Arthur was sworn in as president, serving until March 4, 1885.

Before entering elected politics, Arthur was a member of the Stalwart faction of the Republican Party and a political protégé of Roscoe Conkling, rising to Collector of the Port of New York, a position to which he was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant. He was then removed by the succeeding president, Rutherford B. Hayes, in an effort to reform the patronage system in New York.

To the chagrin of the Stalwarts, the onetime Collector of the Port of New York became, as President, a champion of civil service reform. He avoided old political cronies and eventually alienated his old mentor Conkling. Public pressure, heightened by the assassination of Garfield, forced an unwieldy Congress to heed the President. Arthur's primary achievement was the passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act. The passage of this legislation earned Arthur the moniker "The Father of Civil Service" and a favorable reputation among historians.

Publisher Alexander K. McClure wrote, "No man ever entered the Presidency so profoundly and widely distrusted, and no one ever retired... more generally respected." Author Mark Twain, deeply cynical about politicians, conceded, "It would be hard indeed to better President Arthur's administration." [1]

Early life and education

Chester Alan Arthur was the son of Irish-born preacher William Arthur (born in Cullybackey, Ballymena, County Antrim) and Vermont-born Malvina Stone Arthur. Malvina's grandfather, Uriah Stone, fought for the Continental Army during the American Revolution and named his son, Malvina's father, George Washington Stone. Malvina's mother was part Native American.[2]:4 At the time of the birth of the future president, Arthur's father was an Irish subject of the United Kingdom of Scottish descent, who naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1843.[3]

Arthur's restored ancestral home from the late 18th Century is in County Antrim in Northern Ireland. An interpretive center at the cottage tells the story of the Arthur family, and provides visitors with demonstrations of life in Ireland over the last 200 years.[4]

Most official references list Arthur as having been born in Fairfield in Franklin County, Vermont on October 5, 1829. However, some time in the 1870s Arthur changed it to 1830 to make himself seem a year younger.[2]:5[5] His father had initially migrated to Dunham, Lower Canada, where he and his wife at one point owned a farm about 15 miles (24 km) north of the U.S. border.[2]:4 There has long been speculation that the future president was actually born in Canada and that the family moved to Fairfield later. If Arthur had been born in Canada, some believe that he would not have been a natural-born citizen (interpreting the law to mean that to be a natural-born citizen one must be born on U.S. territory) and would thus have been constitutionally ineligible to serve as vice president or president. During the 1880 U.S. presidential election a New York attorney, Arthur P. Hinman, was hired to explore rumors of Arthur's foreign birth. Hinman alleged that Arthur was born in Ireland and did not come to the United States until he was fourteen years old. When that story failed to take root Hinman came forth with a new story that Arthur was born in Canada. This claim also fell on deaf ears.[2]:202–203 In any case, Arthur's father was not naturalized until some years after his birth, resulting in Arthur having dual citizenship.

Arthur spent some of his childhood years living in Perry, New York. One of Arthur's boyhood friends remembers Arthur's political abilities emerging at an early age:

When Chester was a boy, you might see him in the village street after a shower, watching the boys building a mud dam across the rivulet in the roadway. Pretty soon, he would be ordering this one to bring stones, another sticks, and others sod and mud to finish the dam; and they would all do his bidding without question. But he took good care not to get any of the dirt on his hands. (New York Evening Post, April 2, 1900)

Chester Arthur's Presidency was predicted by James Russel Webster, a Perry resident. A detailed account of this prediction is found in a self-written memorial for Webster.[6] An excerpt from Webster's memorial:

He first attended the Baptist church in Perry, the pastor there being "Elder Arthur", father of Chester A. Arthur. The latter was then a little boy, and Mr. Webster, once calling at his house, put upon his head of the lad, remarked, "this little boy may yet be President of the United States." Years after, calling at the White House, he related the circumstances to President Arthur, who replied that he well remembered the incident although the name of the man who thus predicted his future had long since passed from his memory; then standing up he added. "You may place your hand upon my head again."

He went to prep school at the academy in Union Village (now the village of Greenwich in southern Washington County NY), and then to the Lyceum, where he was known as Chet. During his time at Lyceum Arthur joined other young Whigs in support of Henry Clay and even participated in a melee against those opposed to Clay.[2]:8

Arthur attended Union College in 1845 where he studied the traditional classics. As a senior there in 1848, at age 18, he was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and president of the debate society. He often donned a green coat to show his support for the Fenian Brotherhood.[2]:8

While living outside of Hoosick Falls, New York, he went back to Union College and received his Master's degree in 1851.

Early career

Arthur became principal of North Pownal Academy in North Pownal, Vermont in 1849. He studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1854 after attending State and National Law School in Ballston Spa, New York. Arthur commenced practice in New York City.

A champion of civil rights, Arthur was one of the attorneys who successfully represented Elizabeth Jennings Graham; her lawsuit, after being denied seating on a streetcar due to her race, contributed to the desegregation of New York City public transportation.[7] In Lemmon v. New York, the "Lemmon Slave Case", Arthur helped secure the 1860 decision that slaves being transferred to a slave state through New York would be emancipated.[8] Arthur also took an active part in the reorganization of the New York Militia.

During the American Civil War, on April 4, 1862, Arthur was appointed by Gov. Edwin D. Morgan Inspector-General of the State Militia, and on July 22 transferred to the office of Quartermaster-General of the State Militia, remaining in this office until the end of the year.[9] Both offices, although political appointments, carried the rank of brigadier general. After the war, he resumed the practice of law in New York City. With the help of Arthur's patron and political boss Roscoe Conkling, Arthur was appointed by President Ulysses S. Grant Collector of the Port of New York in 1871, and remained in office until his removal by President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1878.

This was an extremely lucrative and powerful position at the time, and several of Arthur's predecessors had run afoul of the law while serving as collector. Honorable in his personal life and his public career, Arthur sided with the Stalwarts in the Republican Party, which firmly believed in the spoils system even as it was coming under vehement attack from reformers. He insisted upon honest administration of the Customs House but nevertheless staffed it with more employees than it really needed, retaining some for their loyalty as party workers rather than for their skill as public servants.

The 1880 election and vice presidency

In 1878, Grant's successor, Rutherford B. Hayes, attempted to reform the Customs House. He ousted Arthur, who resumed the practice of law in New York City. Conkling and his followers tried to win back power by the nomination of Grant for a third term at the 1880 Republican National Convention, but without success. Grant and James G. Blaine deadlocked, and after 36 ballots, the convention turned to dark horse James A. Garfield, a long time Congressman and General in the Civil War.

Knowing the election would be close, Garfield's people began asking a number of Stalwarts if they would accept the second spot. Levi P. Morton, on Conkling's advice, refused, but Arthur accepted, telling his furious leader, "This is a higher honor than I have ever dreamt of attaining. I shall accept!"[10] Conkling and his Stalwart supporters reluctantly accepted the nomination of Arthur as vice president. Arthur campaigned hard for his and Garfield's election, but it was a close contest, with the Garfield-Arthur ticket receiving a nationwide plurality of fewer than ten thousand votes.

After the election, Conkling began making demands of Garfield as to appointments, and the Vice President–elect supported his longtime patron against his new boss. According to Ira Rutkow's recent biography of Garfield, the new president disliked the vice president, and he would not let him into his house.

Then, on July 2, 1881, President Garfield was shot in the back by Charles J. Guiteau, who shouted: "I am a Stalwart of the Stalwarts... Arthur is president now!"[11] Arthur's shock at the assassination was augmented by his mortification at Guiteau's claim of political kinship. (Madmen and Geniuses, Barzman, 1974) Garfield initially survived the shooting, but due to a combination of infections and the poor medical care of the time, he gradually deteriorated and died on September 19.

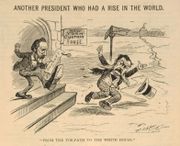

In an 1881 Puck cartoon, Vice President Arthur faces the presidential cabinet (from left to right, Wayne MacVeagh, William Windom, James G. Blaine, Thomas Lemuel James, Samuel J. Kirkwood, Robert Todd Lincoln, William H. Hunt) after President James A. Garfield was assassinated. On the wall hang three portraits of (left to right) Andrew Johnson, Millard Fillmore, and John Tyler, three other vice-presidents who succeeded to the presidency. A fourth frame hangs next to Johnson with no picture and a question mark underneath meant for Arthur's portrait.

Presidency 1881–1885

Arthur was aware of the factions and rivalries of the Republican Party, as well as the controversies of cronyism versus civil service reform. Entering the presidency, Arthur believed that the only way to garner the nation's approval was to be independent from both factions. Arthur was determined to go his own way once in the White House. He became a man of fashion in his manner of dress and in his associates; he was often seen with the elite of Washington, D.C., New York City, and Newport. To the indignation of the Stalwarts, the onetime Collector of the Port of New York became, as President, a champion of civil service reform.

Assumption of office

President Arthur took the oath of office twice. The first time was at his Lexington Avenue residence, when it was given just past midnight on September 20. The oath was given by New York Supreme Court justice John R. Brady. The second time was two days later after he returned to Washington. This time it was given in the Capitol by Chief Justice of the United States Morrison Waite. This was to avoid any dispute over whether the oath was valid if given by a state official. (A similar situation later occurred with Calvin Coolidge.)

Cabinet

Arthur requested that Garfield's cabinet and appointees delay their resignations until Congress convened in December.[2]:254 However, shortly after this request Treasury Secretary William Windom and Attorney General Wayne MacVeagh submitted their resignations. Ulysses S. Grant recommended John Jacob Astor III to be the new Treasury Secretary, but Arthur preferred Edwin D. Morgan. Morgan declined the offer twice, but Arthur submitted it to the Senate anyway, and Morgan was confirmed. Morgan, age 72, still refused. The cabinet position was then awarded to Stalwart Charles J. Folger (October 27).[2]:254 MacVeagh's replacement, Benjamin Harris Brewster, another stalwart, was confirmed two months later.[2]:255

Although Secretary of State Blaine agreed to delay his resignation, he changed his mind in mid-October. Conkling felt he himself was the obvious choice to replace Blaine, but Arthur felt such nepotism would disgrace the presidency and selected Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen, another stalwart, recommended by Grant.[2]:256

The next to resign was Postmaster General Thomas Lemuel James, whom Arthur had tried to renominate. Arthur nominated Timothy O. Howe, another stalwart and a long-time friend.[2]:257 For Secretary of the Navy, Arthur nominated William E. Chandler, a recommendation from Blaine which gave some factional balance to the administration. Grant, who had recommended Edward Fitzgerald Beale, was upset by the Chandler pick and never fully forgave Arthur for the offense.[2]:258

Robert Todd Lincoln as Secretary of War was the only member of the Garfield cabinet to continue under Arthur.[2]:259 He was the only member of Arthur's cabinet who was never replaced and served until the end of Arthur's term in 1885.

Domestic issues

Tariff

Acting independently of party dogma, Arthur also tried to lower tariff rates so the government would not be embarrassed by annual surpluses of revenue. Congress raised about as many rates as it trimmed, but Arthur signed the Tariff Act of 1883 anyway. Aggrieved Westerners and Southerners looked to the Democratic Party for redress, and the tariff began to emerge as a major political issue between the two parties.

Civil service reform

Civil Service Reform had been a burning issue since the Grant administration and both Hayes and Garfield took smaller steps to wrangle in the corrupt and inefficient Patronage system in Washington. Arthur at first was skeptical of Civil Service reform, having been a member of the Stalwarts wing of the Republican party.[12] Arthur, however, realized that reform was vital after the Republicans lost seats in the mid-term election of 1882. The Pendleton Act of 1883 was written by a Democrat, Senator George Pendleton, and "banned salary kickbacks, apportioned federal appointments among the states, and ruled that new employees must begin their service at the bottom of the career ladder, advancing only by merit exams." [13] The passage of this reform became the single most important act in Arthur's presidency. The great irony is that Arthur, a product of the Spoils System, was just the man to end patronage. By standing up to his own friend Roscoe Conkling and wing of the Republican Party, Arthur showed remarkable independence from political forces.

Though it established a bipartisan Civil Service Commission which forbade levying political assessments against officeholders and created a written examination system, the initial effects were less outstanding than many believe. Gerald Bahles of the Miller Center of Public Affairs writes that because the legislation was "not retroactive, present (primarily Republican) incumbents could remain in office even if the Democrats won the forthcoming presidential election."[14] In addition, the Pendleton Act did not cover state or municipal workers and even exempted many federal officials. Despite these imperfections the Pendleton Act was a huge leap forward, spelling the end of the Spoils System.

Civil rights

Chester Arthur signed the Edmunds Act that banned bigamists and polygamists from voting and holding office. The act was specifically enforced in Utah, a highly populated Mormon territory and established a five-man "Utah commission" to prevent bigamists and polygamists from voting.[15]

The Arthur Administration enacted the first general Federal immigration law. Arthur approved a measure in 1882 excluding paupers, criminals, and the mentally ill.

In response to anti-Chinese sentiment in the West, Congress passed a Chinese Exclusion Act. The act would have made illegal the immigration of Chinese laborers for twenty years and denied American citizenship to Chinese Americans currently residing in the United States who were not already citizens and who were not born in the United States.[15] Arthur vetoed this steep restriction on the grounds that it violated the Burlingame Treaty. He was immediately denounced by newspapers in California. When a compromise restriction of ten years was proposed, Arthur agreed and signed the revised bill, however the Chinese Americans residing in the United States were denied citizenship.[15] The Act was renewed every ten years until the National Origins Act of 1924 essentially eliminated Chinese immigration because the quotas were based on the 1890 numbers. The Act had remarkable staying power and was not fully repealed until sixty-one years later in 1943, by which time the US was an ally of Nationalist China in the fight against Japan during World War II. Under such circumstances, the Act had become an embarrassment to the US, necessitating its repeal.

Arthur was reluctant to enforce the 15th Amendment in the United States Constitution and never attempted while President to overturn "Jim Crow" laws throughout the nation that prevented African-Americans from voting. This may have been caused by a Supreme Court decision to overturn civil right cases and the Civil Rights Act of 1875.

Foreign policy

In relation to Asia and Asians, President Arthur was also in office when the United States became the first Western country to establish diplomatic relations in modern times with Korea, which was then a unified, independent kingdom under the rule of the Joseon Dynasty. This was achieved in 1882 with the signing of the Shufeldt Treaty,[16] named after Commodore Robert W. Shufeldt (1822–95), the principal U.S. negotiator. Korea had existed in a state of virtual hermetic isolation for centuries until 1876, when it was forced to establish diplomatic relations with Japan on an unequal basis. The US maintained full diplomatic relations with Korea until 1905, when the latter became an unwilling protectorate of Japan following the end of the Russo-Japanese War.

In 1884, the International Meridian Conference was held in Washington, D.C. at President Arthur's behest. This established the Greenwich Meridian and international standardized time, both in use today.

Perhaps Arthur's biggest success in foreign policy was the construction of a new, steel navy. After the Civil War the US navy had not been upgraded and so twenty years later the American navy was considered a joke when compared to the mighty armadas of the European powers. Arthur "sought the construction of steam-powered steel cruisers, steel rams, and steel-clad gunboats"[17] and "moved decisively to curb corruption and incompetency within the Navy."[18] In addition, both the Naval War College and the Office of Naval Intelligence was created. For these achievements Arthur was called the "Father of the Steel Navy."[19]

Illness

President Arthur demonstrated that he was above not only factions within the Republican Party, but possibly the party itself. Perhaps, in part, he felt able to do this because of the well-kept secret he had known since a year after he succeeded to the Presidency, that he was suffering from Bright's disease, a fatal kidney disease.[20] Arthur probably first contracted the disease in 1882.[21] While it is impossible to know just when Arthur began to be affected by the disease, Arthur's conduct during the elections of 1879 and 1880 was described as vigorous. Yet during the congressional elections of 1882, from mid-1882 onward, he was clearly not well.[22] The disease accounted for his failure to seek the Republican nomination for president aggressively in 1884.[22] Nevertheless, Arthur was the last incumbent President to submit his name for renomination and fail to obtain it.

Seeks renomination

Arthur sought a full term as President in 1884, but lost the Republican party's presidential nomination to former Speaker of the House and Secretary of State James G. Blaine of Maine. Blaine, however, lost the general election to Democrat Grover Cleveland of New York.

Significant events during presidency

- Shufeldt Treaty (1882)

- Standard Oil Trust (1882)

- Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)

- Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act (1883)

- Civil Rights Cases (1883)

- International Meridian Conference (1884)

- Wabash, St. Louis & Pacific Railway Company v. Illinois (1886)

Administration and Cabinet

| The Arthur Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Chester A. Arthur | 1881–1885 |

| Vice President | None | 1881–1885 |

| Secretary of State | James G. Blaine | 1881 |

| Frederick Theodore Frelinghuysen | 1881–1885 | |

| Secretary of Treasury | William Windom | 1881 |

| Charles J. Folger | 1881–1884 | |

| Walter Q. Gresham | 1884 | |

| Hugh McCulloch | 1884–1885 | |

| Secretary of War | Robert T. Lincoln | 1881–1885 |

| Attorney General | Wayne MacVeagh | 1881 |

| Benjamin H. Brewster | 1881–1885 | |

| Postmaster General | Thomas L. James | 1881 |

| Timothy O. Howe | 1881–1883 | |

| Walter Q. Gresham | 1883–1884 | |

| Frank Hatton | 1884–1885 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | William H. Hunt | 1881–1882 |

| William E. Chandler | 1882–1885 | |

| Secretary of the Interior | Samuel J. Kirkwood | 1881–1882 |

| Henry M. Teller | 1882–1885 | |

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court appointments

- Roscoe Conkling -1882

- Samuel Blatchford - 1882

- Horace Gray - 1882

Other courts

In addition to his two Supreme Court appointments, Arthur appointed four judges to the United States circuit courts, and thirteen judges to the United States district courts.

Social and personal life

Arthur married Ellen "Nell" Lewis Herndon[23] on October 25, 1859. She was the only child of Elizabeth Hansbrough and Captain William Lewis Herndon USN. She was a favorite niece of Commander Matthew Fontaine Maury, USN of the United States Naval Observatory where her father had worked.

In 1860, Chester Arthur and "Nell" had a son, William Lewis Herndon Arthur, who was named after Ellen's father. This son died at age two of a brain disease. Another son, Chester Alan Arthur II, was born in 1864, and a girl, named Ellen Hansbrough Herndon after her mother, in 1871. Ellen Arthur died of pneumonia on January 12, 1880, at the age of 42, twenty months before Arthur became President. Arthur stated that he would never remarry and, while in the White House, asked his sister Mary Arthur McElroy, the wife of writer John E. McElroy, to assume certain social duties and help care for his daughter. President Arthur had a memorial to his beloved "Nell" – a stained glass window installed in St. John's Episcopal Church within view of his office and had the church light it at night so he could look at it. The memorial remains to this day.

Arthur is remembered as one of the most society-conscious presidents, earning the nickname "the Gentleman Boss" for his style of dress and courtly manner. Professor Marina Margaret Heiss at the University of Virginia lists Arthur as an example of an INTJ personality.[24]

Upon taking office, Arthur did not move into the White House immediately. He insisted upon its redecoration and had 24 wagonloads of furniture, some including pieces dating back to John Adams' term, carted away and sold at public auction.[25] Former president Rutherford B. Hayes bought two wagonloads of furniture which today are at his home Spiegel Grove. Arthur then commissioned Louis Comfort Tiffany to replace them with new pieces. A famous designer now best-known for his stained glass, Tiffany was among the foremost designers of the day.[26]

Arthur was a fisherman who belonged to the Restigouche Salmon Club and once reportedly caught an 80-pound bass off the coast of Rhode Island.

By the end of his presidency, Arthur had acquired wide personal popularity. On the day he left office, four young women (ignorant of Arthur's pledge not to marry again) offered to marry him. He was sometimes called "Elegant Arthur" for his commitment to fashionable attire and was said to have "looked like a president." He reportedly kept 80 pairs of pants in his wardrobe and changed pants several times a day. He was called "Chet" by family and friends, and by his middle name, with the stress on the second syllable ("Al-AN").

Physical health

As president, Arthur alleviated his stress by taking late evening walks that usually began after 1 AM. He rarely went to bed before 2 AM.[2]:274 However, by the summer of 1882 Arthur was often ill and exhausted, and by the beginning of 1883 he looked emaciated and aged.[2]:318 That March he had attacks from hypertensive heart disease and glomerulonephritis. Officially, Arthur was said to have a cold.[2]:355 In April he took a vacation to Florida for some rest. The trip was cut short when he was hit with severe pain. The White House criticized the media's sensationalism on the matter and blamed the illness on over exposure and seasickness.[2]:358 In October it was revealed to the press that Arthur had been diagnosed that summer with Bright's disease.[2]:317 In a private conversation shortly after James G. Blaine's nomination for the 1884 presidential election Arthur confided in Frank B. Conger that his disease was in an advanced stage and he only had a few months to live, and by the end of his presidency Arthur's health had deteriorated significantly.[2]:381

Post presidency

Arthur served as President through March 4, 1885. Upon leaving office, he returned to New York City to serve as counsel to his old law firm. However, he was often indisposed because of his Bright's disease. He managed a few public appearances but none after the end of 1885.[2]:417 After summering in New London, Connecticut he returned (October 1, 1886) quite ill. On November 16, by his order, nearly all of his papers, personal and official, were burned. The next morning he suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage and never regained consciousness. He died the next day.[2]:418 His post presidency was the second shortest, longer only than that of James Polk who died 103 days after leaving office.

On November 22, a private funeral was held at the Church of the Heavenly Rest. His pallbearers were Walter Q. Gresham, Robert Todd Lincoln, William E. Chandler, Frank Hatton, Benjamin H. Brewster, Philip Sheridan, Cornelius Rea Agnew, Cornelius Newton Bliss, Robert G. Dun, George H. Sharpe, Charles Lewis Tiffany and Cornelius Vanderbilt. Also in attendance were President Grover Cleveland, former President Rutherford B. Hayes, Benjamin Franklin Butler, Chief Justice Morrison Waite, Justices Samuel Blatchford and John Marshall Harlan, Roscoe Conkling and James G. Blaine.[2]:418

Chester was buried next to Ellen in the Arthur family plot in the Albany Rural Cemetery in Menands, New York, in a large sarcophagus on a large corner plot that contains the graves of many of his family members and ancestors. Sculptor Ephraim Keyser designed the sarcophagus.

Writings and sayings

On Taxes and Spending:

- "The extravagant expenditure of public money is an evil not to be measured by the value of that money to the people who are taxed for it."[27]

On Democracy:

- "Men may die, but the fabrics of free institutions remain unshaken."[28]

On Privacy:

- "I may be President of the United States, but my private life is nobody's damned business."[27]

On Garfield's death:

- "An appalling calamity has befallen the American people since their chosen representatives last met in the halls where you are now assembled...To that mysterious exercise of His will which has taken from us the loved and illustrious citizen who was but lately the head of the nation we bow in sorrow and submission. The memory of his exalted character, of his noble achievements, and of his patriotic life will be treasured forever as a sacred possession of the whole people." [29]

On Sitting Bull:

- "The surrender of Sitting Bull and his forces upon the Canadian frontier has allayed apprehension, although bodies of British Indians still cross the border in quest of sustenance. Upon this subject a correspondence has been opened which promises an adequate understanding. Our troops have orders to avoid meanwhile all collisions with alien Indians."[29]

On the Interoceanic Waterway:

- "The questions growing out of the proposed interoceanic waterway across the Isthmus of Panama are of grave national importance. This Government has not been unmindful of the solemn obligations imposed upon it by its compact of 1846 with Colombia, as the independent and sovereign mistress of the territory crossed by the canal, and has sought to render them effective by fresh engagements with the Colombian Republic looking to their practical execution."[29]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- Arthur Cottage, ancestral home, Cullybackey, County Antrim, Northern Ireland

- List of Presidents of the United States

- U.S. Presidents on U.S. postage stamps

References

- ↑ Chester A. Arthur in Office

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. NY, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-46095-2.

- ↑ Cf. William Arthur's certificate of naturalization, State of New York, 08-31-1843, in: The Chester A. Arthur Papers, Library of Congress, Washington.

- ↑ "Arthur Cottage". discovernorthernireland.com. Northern Island Tourist Board. http://www.discovernorthernireland.com/Arthur-Cottage-Cullybackey-Ballymena-P8218. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ↑ 1830 is the date on his grave inscription and occurs in some reference works.

- ↑ "James R. Webster". USGenWeb Project. http://www.rootsweb.com/~nyseneca/webster.htm.

- ↑ Criscione, Rachel Damon (2006). How to draw the life and times of Chester A. Arthur. New York: Rosen Publishing Group. p. 12. ISBN 1-4042-2998-1. http://books.google.com/?id=HH0GPsw5DaEC. Retrieved October 24, 2009.

- ↑ "President Chester A. Arthur State Historic Site". historicvermont.org. Vermont Division for Historic Preservation. http://www.historicvermont.org/sites/html/arthur2.html. Retrieved October 24, 2009.

- ↑ The New York Civil List compiled by Franklin Benjamin Hough, Stephen C. Hutchins and Edgar Albert Werner (1867; page 401)

- ↑ Sol Barzaman: Madmen and Geniuses; Follet Books Chicago 1974

- ↑ Doyle, Burton T.; Swaney, Homer H. (1881). Lives of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Washington: R.H. Darby. p. 61. ISBN 0-104-57546-8. http://www.archive.org/stream/livesofjamesa00doyle/livesofjamesa00doyle_djvu.txt.

- ↑ http://millercenter.org/academic/americanpresident/arthur/essays/biography/4

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 http://millercenter.org/academic/americanpresident/keyevents/arthur

- ↑ Hyo-wan, Lee (June 13, 2008). "Essays Trace US, Japan Roles in Joseon's Downfall". koreatimes.co.kr (Korea Times). http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/include/print.asp?newsIdx=25829. Retrieved May 23, 2009.

- ↑ http://millercenter.org/academic/americanpresident/arthur/essays/biography/5

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Ibid

- ↑ Thomas C. Reeves, Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1975), pp. 317-318.

- ↑ Thomas C. Reeves, Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur, p. 317.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Thomas C. Reeves, Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur, p. 318.

- ↑ Ellen "Nell" Lewis Herndon's biography via Whitehouse.gov

- ↑ "INTJ personality". http://typelogic.com/intj.html. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

- ↑ "President Chester A. Arthur State Historic Site". Historicvermont.com. http://www.historicvermont.com/sites/html/arthur2.html. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- ↑ Mitchell, Sarah E. "Louis Comfort Tiffany's work on the White House." 2003.[1]

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 [2]|Chester A. Arthur|2009|Chester Arthur Quotes (Chester A. Arthur Quotes)

- ↑ [3]|Chester A. Arthur|2009|Chester Arthur Quotes (Chester A. Arthur Quotes)|

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=29523| Chester A. Arthur| State of the Union Address| December 6, 1881

External links

- Extensive essay on Chester Arthur and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- Chester Arthur: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- Chester A. Arthur at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress Retrieved on 2008-09-28

- White House Biography

- Works by Chester Alan Arthur at Project Gutenberg

- First State of the Union Address of Chester A. Arthur

- Second State of the Union Address of Chester A. Arthur

- Third State of the Union Address of Chester A. Arthur

- Fourth State of the Union Address of Chester A. Arthur

- POTUS - Chester Alan Arthur

- Medical and Health history of Chester A. Arthur

- Chester A. Arthur Historic Site

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James A. Garfield |

President of the United States September 19, 1881 – March 4, 1885 |

Succeeded by Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by William A. Wheeler |

Vice President of the United States March 4, 1881 – September 19, 1881 |

Vacant

Title next held by

Thomas A. Hendricks |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by William A. Wheeler |

Republican Party vice presidential candidate 1880 |

Succeeded by John A. Logan |

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||